The Last Apple Harvest

After twenty-one years, we are leaving this place. And not in the manner I so often feared we might – at our most vulnerable, and with nowhere else to go, like so many before and around us – but through our own agency.

I don’t have to think how long we’ve been here, the years correlate exactly with our middle child’s time on this planet. We signed the contract the day she was born. With the prospect of homelessness on our periphery, my body seemed unwilling to let the baby go. I was unable to walk unaided for two weeks afterwards, and became feverish with a womb infection. My husband began his training for a new job, that same week. Such is the transition from tied accommodation, to rented.

Nine months and three weeks before, my husband had returned from Iraq. As stable hand at a thoroughbred stud farm, he’d also been a paid, volunteer soldier in the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. The call-up shocked us both. But after six months away, he was returned safely, and made the decision to leave the stud farm, and do something else. He was quickly accepted onto a trainee course that would eventually lead to him qualifying as a paramedic. We had under four weeks to find somewhere to live; but we did, just in time. He joked with the new mother of the first baby he delivered, that last time, it had been a royal foal.

In looking for our decades-old tenancy agreement, we find old bank statements. My husband’s new job earned £1,000 a month. Our rent, before any bills, was £800. It’s a small, 2 bed house with a third box-bedroom, and required two month’s rent as a deposit, plus a month’s rent up front. I’d like to say, I don’t know how we did it; only I do. The path is made by walking and barely changed for the next seven years, before it began, slowly, to improve. But it has been a happy place.

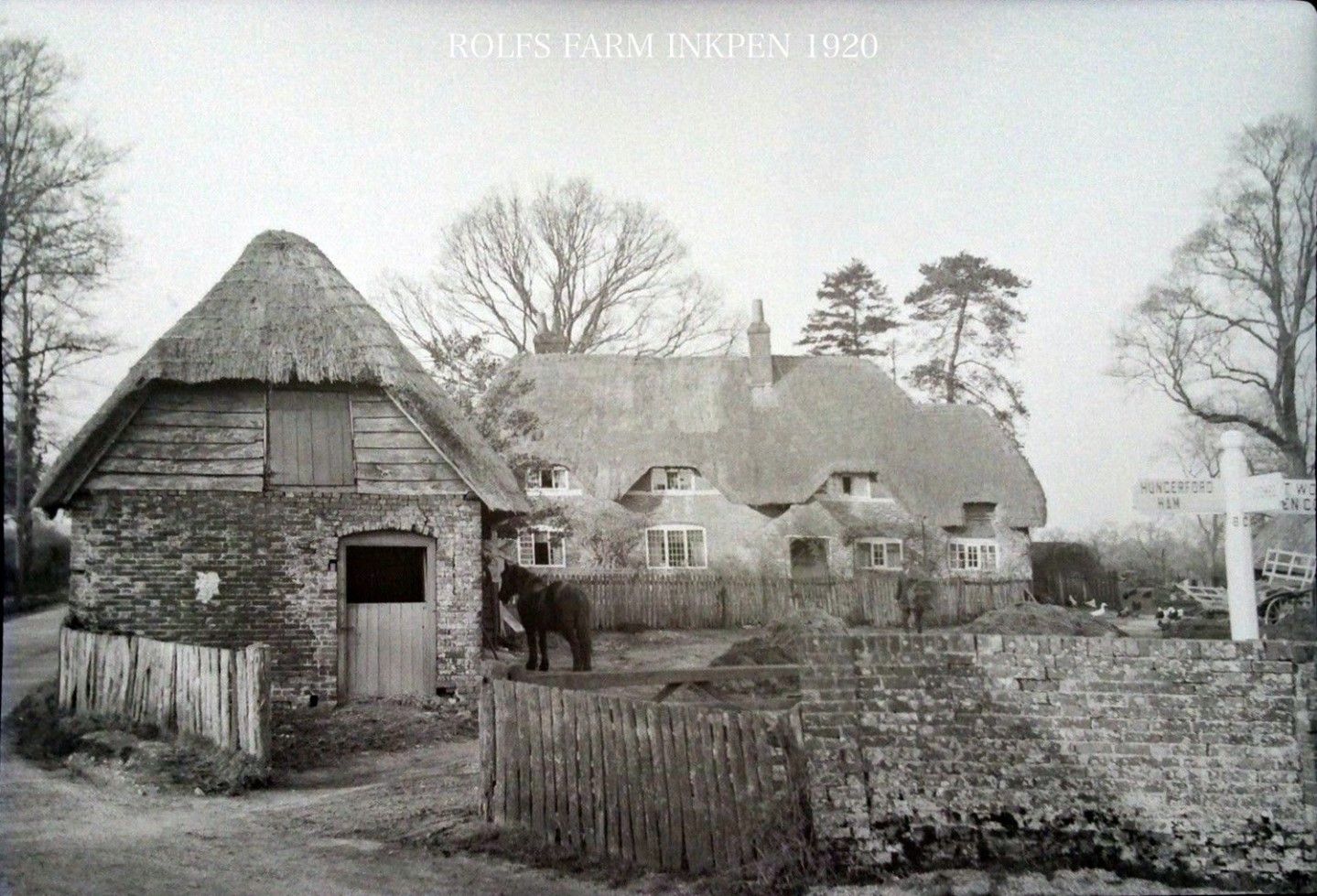

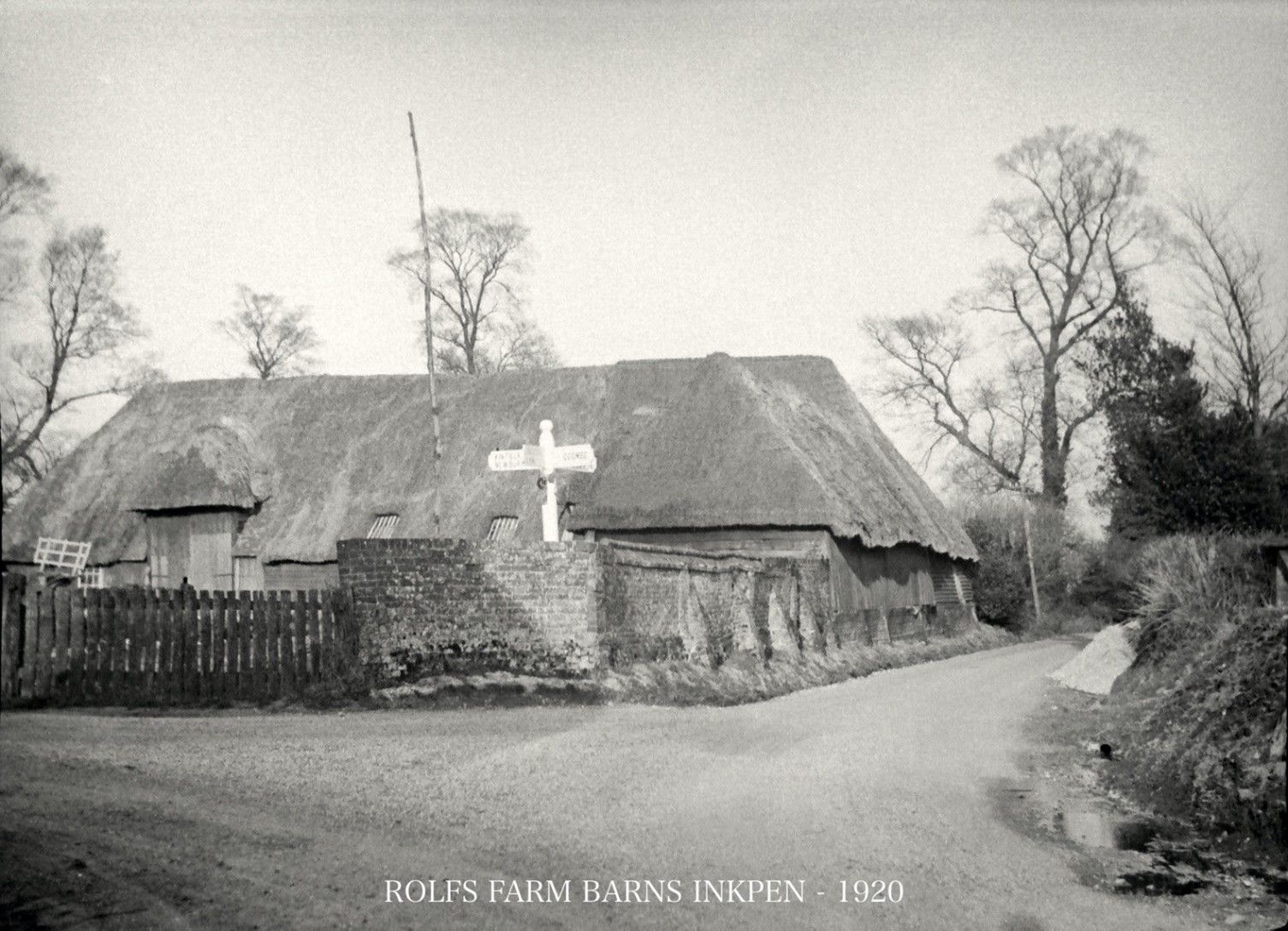

Though it had long since become too small for a modern family of five, it had been an huge social improvement on what had gone before: built in 1953 by Newbury MP John Astor, it was one of six new houses built to replace several damp, cramped, two room cottages, housing large families without electricity or sanitation. An older friend in the village remembers her father holding a lit match to one of the wet cottage walls, to reassure her, as it hissed out, it couldn’t burn down.

As an estate cottage, it came with familiar quirks: until replaced with uPVC, all the wood and ironwork was painted in estate green, matching the other properties on the estate, which often had the same quality, made-to-measure, curtains and blinds. For a long time, we were involved with estate life, could collect firewood and cut our own Christmas tree. We lived mostly out of doors. When we requested to fell a towering, teetering, storm-pushed eucalyptus tree in the back garden, we asked to plant two apple trees. Our landlord agreed, in return, for a peppercorn rent of some fruit.

Since last Christmas, everything has been done ‘for the last time’ and takes on a particular poignancy; an elegiac light. Particularly because we’ve survived the precarity until the end, until we made the decision to go – our three children have grown up here. The attic is yielding boxes of much-loved toys and things we really shouldn’t have held on to. But it is the immediate outdoors we are finding hardest to leave. The last clutch of sparrow chicks, the last broods of starlings from the eaves; the last apples, the last harvest.

Time was, we greeted the combine each year in the field beyond the back garden gate, putting the children on board with the farmer and relishing our own ride round, before jumping the windrows in the evening light, and filling bags with straw for the horses, rabbit and chickens. The billion-bee roar of the combine that lulled us to sleep on hot summer nights, so familiar, we could count the passes by the altered sound of the header lifting for the turn, and knew when the field would be finished; or hear the great machine wind down and know the dewpoint had been reached, or a fine drizzle begun, or that fat thunderplumps of rain were falling; the farmer already down from his cab and walking back to his own lighted cottage.

As we pick the last rosy apples, allowing the boughs to spring back like whips to the sky, the sparrow family have gone for their annual August holiday in Home Field. Camping out in the bender tents of seed-heavy grasses, drinking dew from them in the morning, as if from a slow-dripping farmyard tap, the sparrows remind me of my Grandad’s stories of hop-picking summers. Soon, they’ll be back under the eaves for another eleven months, chirruping and squabbling away in the eaves between our bedrooms. We hear them when we lean out to say goodnight, or watch some fireworks on the hill, or a thunderstorm, sometimes calling out to our neighbours, too.

I don’t know what to do about the sparrows. They are here because we’ve put up boxes, because we’ve grown jasmine and rambling roses up the wall, and what if the landlords or new tenants cut it down, or don’t like the nestboxes? If we took them, we’d be evicting the sparrows, just as we often feared we might be. My plans veer from stuffing the holes with cloth at night and removing them wholesale, to our new place; or beguiling the new tenants with the little birds’ charms – and a rumour of bad luck, should anything happen to them.

Meanwhile, we deliver apples to our neighbours, and pack up, waiting for the older two to come home, for the last time. I play with the word, perdure; new to me. I roll it around. A blend of persistence and endurance in a place, that means it will always be a part of you, and you, it. Our children understand this absolutely, learning from my stubbornness to root, fiercely.

Daft really. In a couple of months, we are moving just under a mile away, to Mum’s house; have pooled our savings and borrowed between us, and built her a little annexe. We are still here. Can still see the big hill from the garden. Are safer. We perdure. And it tastes like each bite of those rosy red apples, sweet and tart, sour with a bruise sometimes, sharp as our memories and love for this place and what it has meant to us. The luck of finding it; of staying.

Leave a comment