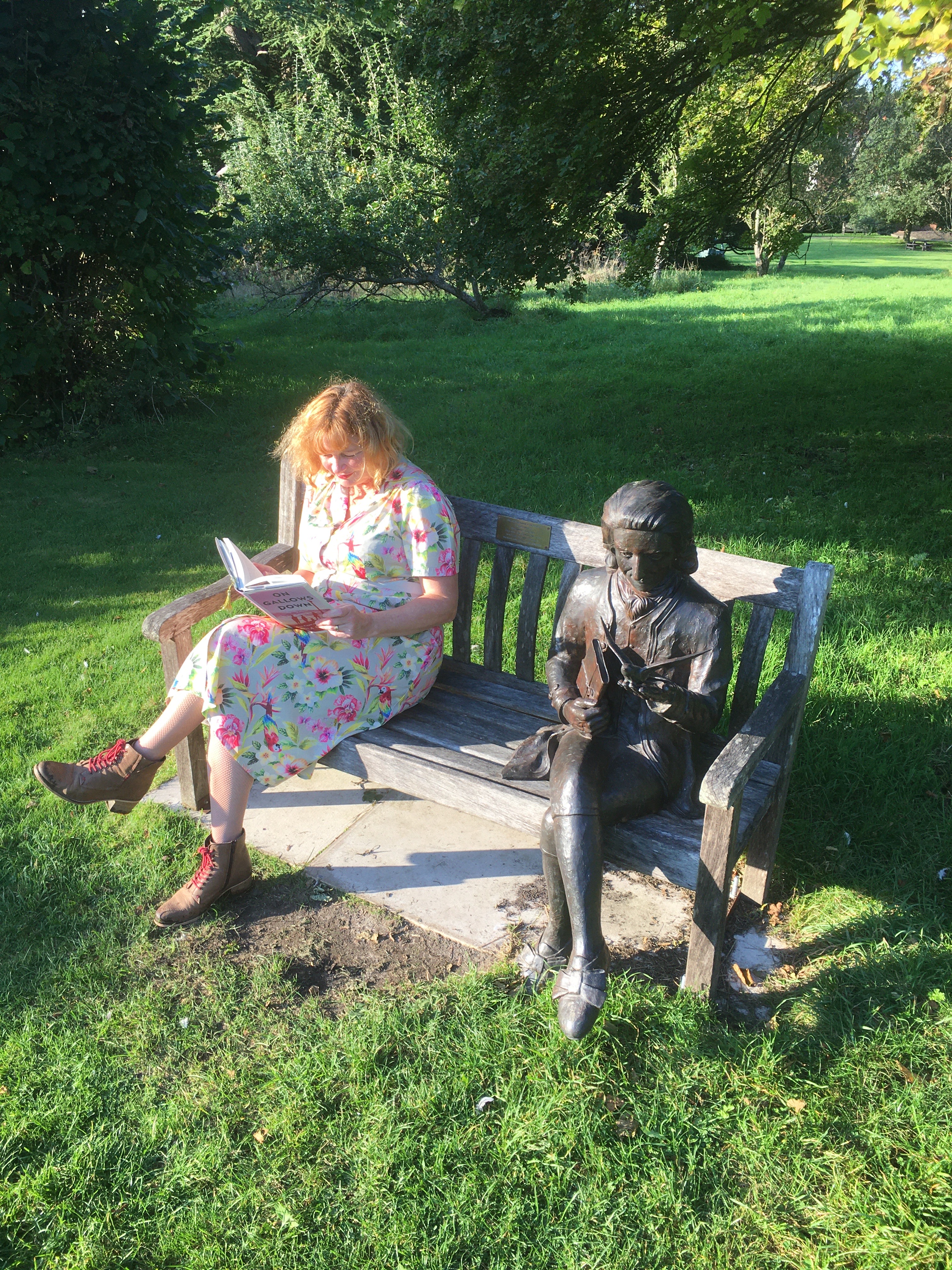

Me, The Gallows Down and Gilbert White.

18 years ago, I won BBC Wildlife Magazine’s Nature Writing Award, for a piece on bringing up my young son, ‘with nature’, and the hope that came from the ‘giving back’ of Greenham Common to both people and wildlife. I’d known Greenham Common before it was enclosed, before the missiles came, and before the Peace Women came – and stayed for 19 years. Their tenacity, humour and strength inspired me to make my own protests against the loss of nature (on Newbury Bypass particularly) and I’ve not stopped since. This month, my book, On Gallows Down, is published, and the first review of it appears in that very same magazine. The book took 8 years to write, in the gaps between everything else. I was always in this for the long haul. And much of what’s in the book has been inspired by this column that I’ve kept, for 17 years, too.

It seems a pertinent time: 40 years since the Peace Women made their historical march to Greenham, and stayed; 25 years since the Bypass Protests began, and 21 years since I set foot on the open Common again, after (joyfully, against the odds) it was returned.

Writing a column like this, for such a long time, is a deep privilege. Detailed, local observations can be writ large against what is happening in the wider world – as with any ‘local’ story: it’s a homing in on the details and chronicling them; a bearing witness. Core drilling.

The weekend before the book launch and tour, we get away, and I find myself in an orchard of ancient mulberry trees, half a century old, in a hotel garden in Evesham.

There are robins singing softly, and church bells; and a red mulberry leaf turns in the breeze, suspended by a golden cobweb thread. I try to take stock, think all the things, & let the season turn, the pendulum swing.

We wander (unhurried for once) around an enormous medieval tithe barn built of blue lias limestone, and dressed in Cotswold marl, probably in 1250. Its roof soars: a complicated forest of oak rafters, an upturned, dry ark.

Light streams through slit windows and square ‘putholes’, that bore scaffolding beams to build it. It is cathedral like and breathtaking. Protective ‘witch marks’ are carved into a lintel. I think about this little unfamiliar parish, and all the harvests, hardships and hurrahs this barn has known. All that dust still stirring, not settling, in shifting beams of light.

Turning for home, the car headlights sweep the chalk and straw bends into the softest laser beams. The amber moon waits above the gate like a boiled sweet. And where the old, tarred & black-raftered Berkshire barn once stood; inexplicably, its outline.

And then, on a golden, October afternoon, I’m waiting on a window seat, in the Great Parlour of Gilbert White’s house, in a stream of light. I’m about to give a talk on my newly published book, and am feeling more than a little awed. I make pilgrimages here. The Reverend Gilbert White was a pioneering naturalist, the ‘Father of Ecology:’ his book, The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne was published in 1789 and has not been out of print, since.

Charles Darwin was a fan. David Attenborough and Chris Packham are. And here I am.

I wonder at the connection between us, between all lovers of nature. Gilbert White made close, local, detailed observations and understood the importance of connectivity and the perpetual significance of things bigger than he was. He enjoyed the idea of exploration but was afflicted by debilitating travel sickness. And he was a community man, invested in his parish; so he travelled without going anywhere much. He did this through correspondence, conversation and debates, held in this very room. He was a man ahead of his time. He gardened, farmed and didn’t separate nature from anything he did. He studied it much as we do now: not by hunting, killing and collecting specimens, but by observing things in their natural habitat. In this way, he connected to the rest of the world.

During lockdowns, the museum began a hashtag, #BeMoreGilbert, making the link between his local records and what we noticed on our own small patches and repeated perambulations.

It struck me, in the light of that perfect, too-warm October afternoon, motes of a naturalists, tithe barn dust spinning in columns like gnats, that, in many ways, he and I are doing similar things (if I dare make the comparison). But there is a hugely significant difference. He was recording and noting abundance and decoding mysteries; whilst I am recording and noting loss, and trying to get others to act upon what we undeniably know.

Gilbert White advanced the science of Natural History and engaged others, leaving an enormous legacy – while I am desperately chronicling the decline of nature against our increasing recognition of a dependence upon it, as well as our inability as a species to address what it means to us and our survival. His writings are a legacy; a revelment and revelation in the wonder and connectivity of life on earth. I don’t want mine to be an elegy: a eulogy for a dying planet. I want it to drum up resistance to that loss; to inspire a love and hope for it that might allow us to marvel in the sort of discoveries he made: that owls hoot in B flat, for example. Because, down the long, golden room, Gilbert and I are at opposite ends of a long decline.

Leave a comment