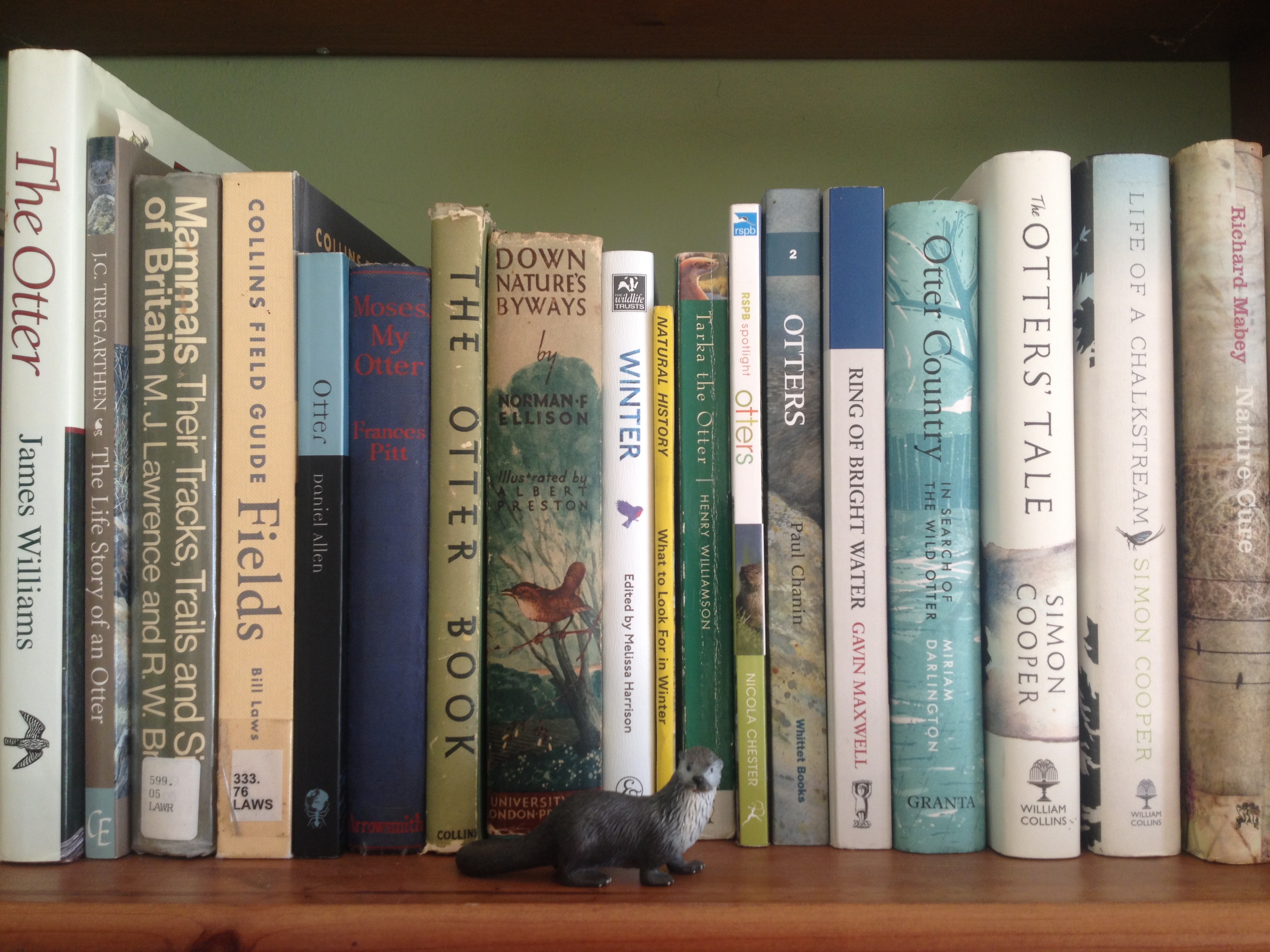

Mercurial, argent: winter chalkstream.

Below the high chalk of the North Wessex Downs, rainwater that has percolated through the porous substrate, flows at a near-constant 10C into benign, gin-clear chalkstreams.

For otters in winter, this is a good thing. And there is potentially a better chance of spotting these elusive, mercurial creatures now: with their super-fast metabolism and evolutionary niche of heat-sapping, riverine living, they must spend much of their time hunting.

I have come down to the river having abandoned a search for hawfinches, somewhat perversely swopping one, hard-to-spot creature for an even harder one. Possibly. But perhaps not this year, when it seems hawfinches are everywhere I am not. I have been haunting churchyard yews, beech hangars and wild cherry holloways, but each time, something has called me away, or the weather has been wrong, the light, lost. I have a creeping, vague feeling I haven’t earned them yet.

Otters are regularly (and irregularly) seen on the Rivers Kennet and Dun that flow through Hungerford. Much of the river is private, but Freeman’s Marsh is just that: a quiet, oozy gem, a free marsh. I should know better than to go out with the aim of seeing a particular creature, because this is when you’re least likely to see them and are in danger of being blinkered to other wonders.

In an hour I glimpse a water vole buoyantly ferrying a width before vanishing and siskins, redpolls and goldfinches in the alder carr: a jewel-box lattice work of birds. Three times, the small, sodium-orange and teal comet of a kingfisher burns past.

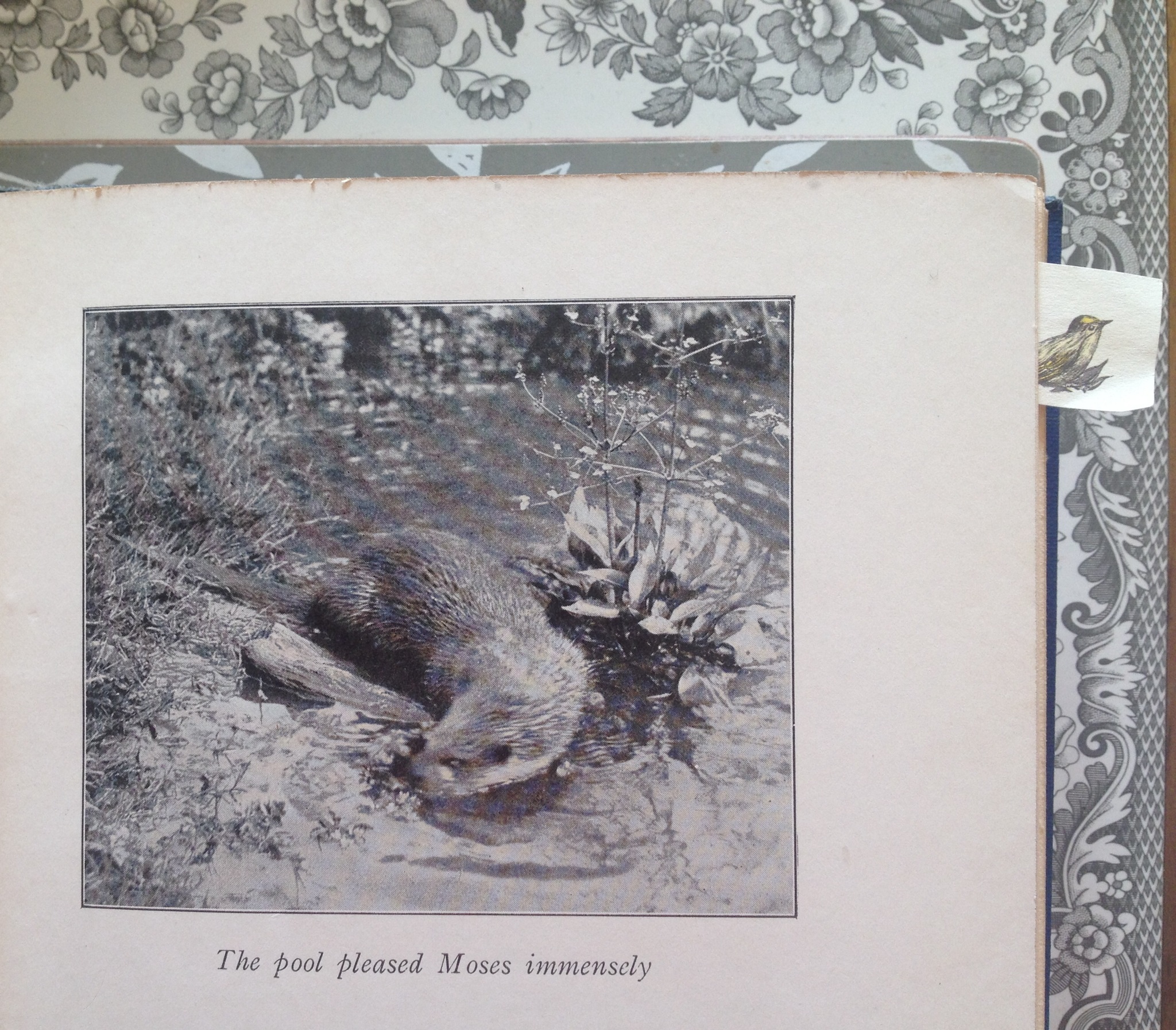

Not so long ago I dreamt every night about otters and thought I saw them in unlikely places. Writing a natural history of them for the RSPB, I felt, for months, as if I had an otter curled up wetly in my brain like a strange hat, leaking river water out over my eyelashes.

The last otter I saw crunched crayfish on the parapet of the road bridge into town at dusk. It disappeared, pouring itself into water and becoming it, before resurfacing under the feathery skirts of a sleep-floating moorhen. Like a practical joke.

The low sun gilds the marsh and lights the river. A grey wagtail bobs on a raft of water crowfoot, its yellow belly a blob of butter reflected in a river, argent and syrupy.

Then the world turns abruptly graphite; pencil drawn. There is the unexpected hiss as a brief snow shower passes. Its sound is startling, as if someone (or something) has swept by in a long coat. A high piping whistle pierces the babble and hiss. I peer hard at the water: the grainy shape of a flat, broad head floats, followed by the bump of a long rump and the hump of a thick tail, Loch Nessie style. Everything whispers otter, but does not shout it. A ripple twists and firms into fur, that melts into water and is sunk, gone downstream on a long-held breath.

Photo: Ann-Marie Haggar

This article is a version of one that appeared in the Saturday Daily Telegraph, 20th January.

Leave a comment